Introductory lecture for the 2021 summer elective “Cultural Landscape of the City” at School of Architecture, cuhk, a course to explore the cross-over of theatre and architecture through spatial exploration of the City as a stage of performance.

I. What is “Cultural Landscape” of the City?

When we talk about cultural architecture – the grand opera house or the new museum in town – they always appears as the LANDMARK, just as we have this magnificent development of West Kowloon Cultural District in Hong Kong with architectural icons from the M+ to the Xiqu Centre. These are all beautiful objects, but then where do we situate ourselves, as a person, in there?

The initial idea for this course is to bring a different perspective on what is “Cultural Landmark” – and from landmark I’d like to propose it as Cultural LANDSCAPE – as space that people actually use. While we can only look at or admire a landmark, there are many different ways to experience landscape. From the perspective of a designer/architect, how can we play with the dynamics of built object and experienced space? — This would be the main question to explore in this course.

We love looking at iconic buildings in Architecture School, mostly masterpiece by great architects around the world, but from the pictures, as an object, from the outside. In this course, we’ll take the understanding of cultural architecture from the exterior FORM to the exterior/interior SPACE. Public space at cultural building is often the site of creative artwork, sometimes in static form of sculpture or installation, or it could be interactive setup or performing arts. Focusing on the public space outside of the standard functional program (i.e. the auditorium and the gallery), we will investigate how cultural space is experienced through different cultural practice. Furthermore, the scope of architecture would be expanded to a broader sense of spatial design as we engage in a short design project.

The exterior plaza space of a cultural landmark is positioned between the prescribed cultural function and generic urban public space. It can be used freely as everyday space, but sometimes also used for formal or informal cultural programs. In this case of the Pompidou, the “piazza” of the building is famous of street performance and artistic events. Public accessibility (and therefore experience) is extended into the interior space of the building, as a conceptually continuous public space from outside to inside. (although nowadays accessibility became easily sacrificed for the sake of security or health…)

There will be two recurring theme in this course:

- Cultural (Architecture) Space: while we will visit some very nice and iconic architecture, please also put on another hat to look at it not as an object but as space.

- Urban (Performance) Stage: as we look into cultural space as inhabited space, how can we as designer (or simply creative citizen), begin to interact/appropriate with these well-curated public space?

II. Public Space in Cultural Buildings

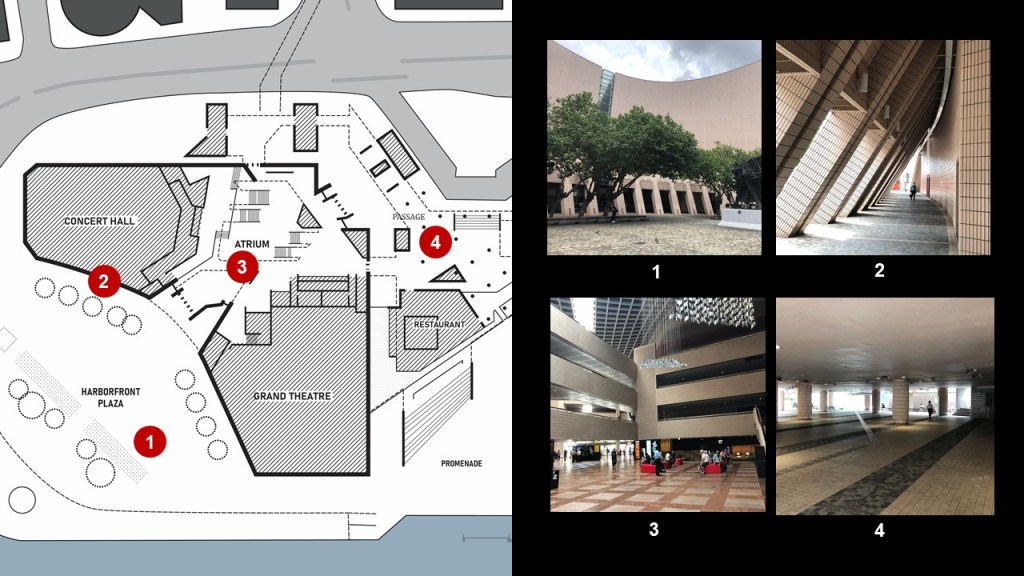

I wonder if you ever passed through the HKCC atrium as a short cut from the Star Ferry to Tsim Sha Tsui – if you think about it, the thorough atrium space of the cultural centre is essentially a part of the urban public space. This type of permeable interior space is also an important part of our urban experience, essentially like a public plaza where people could go inside and sit (or to get cool in hot summer days) without having anything to do with so-called “arts and culture” activities per say.

The plan drawing of the building and its surrounding reveals this special character of public interior, particularly those of cultural institutions. The way this drawing is done hatched the inaccessible functional space (the theatre and concert hall) in porche, then the void space (public and accessible) is revealed as continuous with the outdoor surrounding. This “white space” will be the subject that our investigation would focus on, let’s keep in mind this idea of spatial sequence building up through indoor/outdoor, which shall come back in the discussion of field trip visits.

As we visit the public space at cultural buildings, I’d like you to take note of the continuous space and the architectural elements that create the spatial experience. What is the proportion of the space? How is the transition from outside to inside? What is the element that define this threshold? How about material and lighting? These are the question we could ask as we study the (public) spatial quality of these landmark buildings.

From the static/aesthetic description of spatial quality, what do people do in these spaces and what kind of setting is perceived? In the 18th & 19th century, cultural places like the opera house foyer is the key venue where people could meet and greet. Even today, during events such as the movie premiere or gallery opening, the public area at the theatre or museum is still serving its role as a vibrant social space. One example could be how the atrium and entry stairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is transformed into an extravagance social venue during the Met Gala, celebrities like Lady Gaga in this case with their gowns and costume somewhat similar to the 19th century bourgeois opera audience.

Besides the content (the performance or exhibition) inside a cultural venue, artistic practice often happens outside of the auditorium or gallery. Public space is then transformed into a Public Stage, and the discipline of architecture cross-over with performing arts.

Architecture is defined by the actions it witness as much as the enclosure of its walls.

Bernard Tschumi

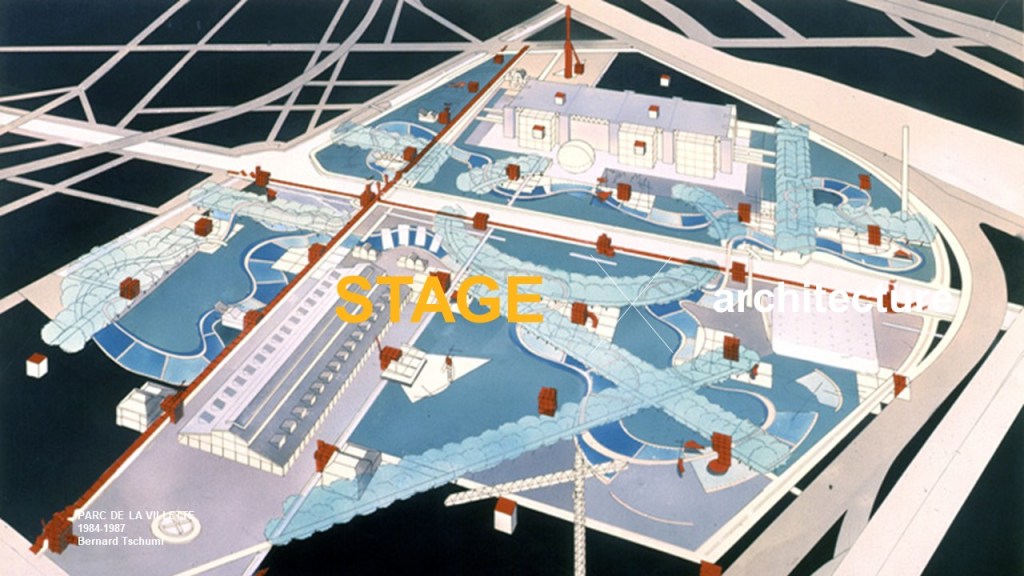

Bernard Tschumi sees the essence of architecture as the action (or performance) that happens in space, and since his early career he explore how action inform space through documentations (Manhattan Transcript), landscape planning (Parc de la Vilette) and built space (Lerner Hall). There is the famous “manifesto” by Tschumi that say “To really appreciate architecture, you may even need to commit a murder” – what he means is of course not that you should kill for architecture, but how events is what makes architectural space come alive.

In Manhattan Transcript (1976-81) he traces the motion of “performance” in the city and translate it into drawings, diagrams and architectural image. Action became the source of spatial creations and this work is regarded as key influence of his later project – Parc de la Villette in Paris, opened in 1988. The park is designed with a framework of the elementary motif of points, lines, and surfaces, layered in a way that it resembles the Manhattan Transcript that freezes movement in space. The Lerner Hall (1999) at Columbia University goes beyond the internal function as a student centre, embracing the idea of “in-between” space by placing corridors and ramps on the street-facing facade, allowing the action of users to be “on display”.

III. Learning from the Stage and its Space

There is a tradition in how architecture response to theatre, or the emphasis of theatrical spatial effects in architecture. Can we take the language of theatre design to think about architecture? In many cases, artistic endeavour (particularly in theatre but not limited to) use space to narrate and the space created in contemporary performing arts is no long a representation of a certain “setting” but speaks for itself. With less constrain of the industry, theatre space have the opportunity to practice purely on spatial construct, somewhat even more architectural. As the main concern of theatre work is usually the character – the person, spatial design for stage became an agent to enhance the movement and the narrative. Through a series of work by Belgium theatre director Ivo van Hove and his scenographer Jan Versweyveld, we can see what are the spatial elements that is used in these theatre pieces. It might sound familiar to you as how they could also be spatial language we use in architectural projects.

The actual “story” of these work to us is less important as we would focus on the spatial construct of these different works. The role of “stage design” is no longer to create a “realistic set” to imitate the setting – which is fundamentally a conflict to represent reality in a space that is essentially non-real…

ABSTRACTION

The first piece of work is A View from the Bridge, an adoption of Arthur Miller’s novel that was set in 1960s Brooklyn. Instead of a “set” with period furniture to imitate the time and space of a 1960s American family sitting room, the scenography presented a minimalistic rectangular frame that serves as all the scenes, working with dramatic light to define different spatial atmosphere. The stage designer emphasis on being “truthful” in his design, and not in a way to mimic physically, but to be true to the space and material of a theatre, and the narrative (emotion). The approach to construct space is something we frequently refer to in architectural design – abstraction. It gives the idea of a “scene” through minimal details, and it is not only the “background” of the narrative but it is a part of the story. It is even more fun as the stage is not static, the components will move. Working with other theatre elements such as light and even water, the abstract design can give audience the mental space to think and immersed into the work.

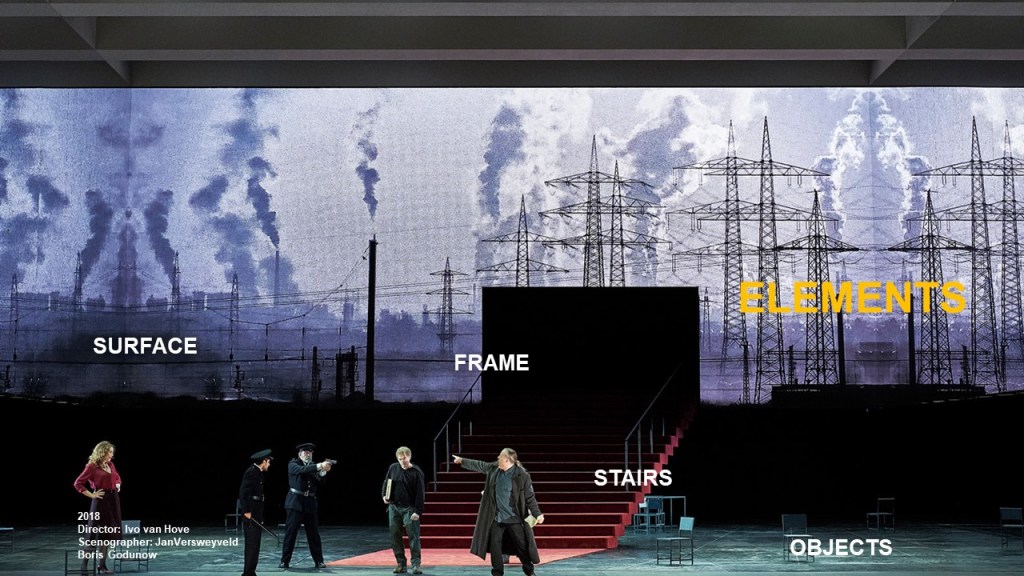

ELEMENTS

In this other production Boris Godounov, a classic opera about Russian monarchy, there is no golden fixtures or the grandiose staircase of a palace – these intention and drama is represented by the simple spatial elements. Nowadays with advance in stage technology, the “backdrop” of traditional theatre become the digital screen, which has opens up another whole new dimension of the depth of space. The surface also allows for an opening, to create a threshold condition that is important in theatre to portrait entry/exit of the character. The stairs as a structure works to allow actions such as ascension or descension, or the position above or below to represent power relations in a monarchy story. A collection of repetitive objects are used to loosely define space and relation, also flexible items that can work with the actor’s motion. These elements speaks to the essence of movement and positions, without the need of any decorative details.

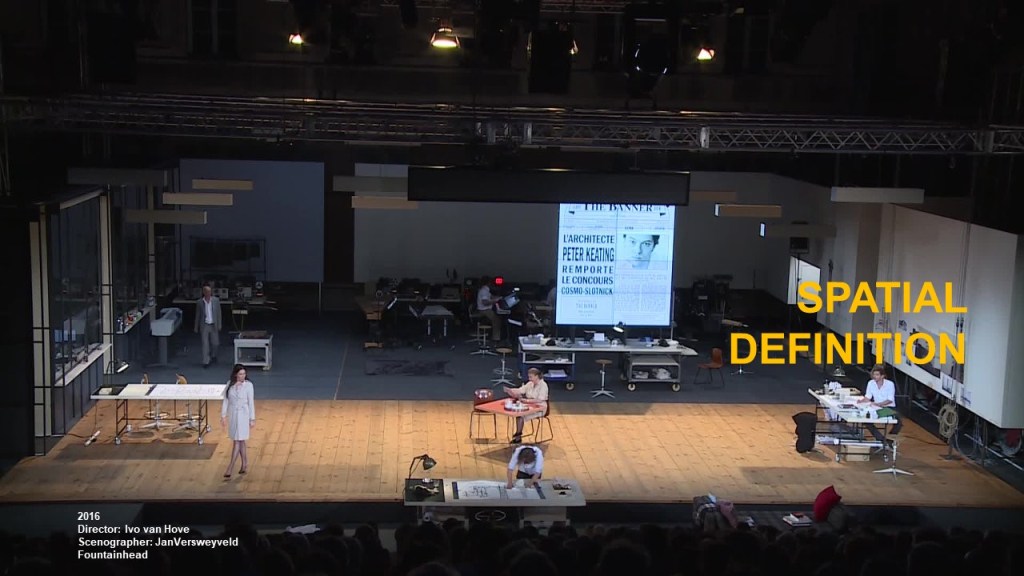

SPATIAL DEFINITION

In Fountainhead, another story set in the 1960s American city about an architect’s persistence on his vision, elements of the surface/threshold/structure are used differently, from a more frontal view of the previous work into a rather expansive and horizontal spatial structure. The floor – horizontal surface is delineated with different material to define foreground and background, which also exaggerated horizontality. One side of the wall is solid with sketches as in the studio, but it does not go all the way to the ground and left a space in between, giving sufficient spatial definition yet not totally boxed in. The other side is the window frames, also define (and physically divide) space, but visually transparent and the transparency allows for lighting to create a strong flood for the theatrical climax. There is no ceiling in a stage set per say, but space above can also be defined, in this case by a regular grid of light bars.

It is a stage set, but also very architectural, isn’t it?

There seems to be more commonality between architecture and the stage, and they do overlap more in certain cases. The Damned is a theatre work that is taken out of the theatre and staged in actual space, at this outdoor venue of the old palace courtyard during the Festival Avignon. The different language of stage design is still applied here, but the surrounding environment is absorbed into part of the theatrical space… which leads to the question of how Urban Space become Urban Stage, or how do we interact with the city through performance?

IV. Stage, Performance and the City

This bring us back to the idea about urban space and architecture, and the opportunity to appropriate cityscape through cultural practice. Artist do that a lot, from placing an object or artwork in the city (as traditional sculpture does), to installation work that interacts with urban space. It’s more common in visual arts rather than performing arts to incorporate actual urban spatial elements into the work, yet the boundary of different art form is also dissolving.

Beyond the static work, performing arts challenge the spatial appropriation further with the element of the performance – by placing a person in space the dynamic is ever-changing. Instead of creating a stage space for the performance, the work has to accommodate the environment, although it is often a welcoming challenge for the creative mind, and the given spatial condition became an inspiration for how the person to react and interact. The work Rice, by Taiwanese dance company Cloud Gate, is a an experience of putting up a performance in the middle of a rice field in east Taiwan. With very minimal adaptation, the country space became stage space for a dance about the life and works of rice padder farmers.

The last work to share with you today is another dance performance in urban space. It is in fact a documentary film by German director Wim Wenders about the Pina Baush dance company. Besides some footage of rehearsal or performance of the company, the film took the dancer and place them in different urban space. The interaction of the performer and the city became then staged, with the director’s eye to position the cityscape within the camera frame and the dancer to “dance with” spatial elements. It is also a documentary about the German town Wuppertal where the company is based at, as well as famous architecture designed by SANAA, which those fascinating spatial quality is brought out by the dynamic movement – as the architecture became alive.

Playlist during work sessions:

- Ivo van Hove & Jan Versweyveld – A View from the Bridge

- Pina 3D by Wim Wenders of the choreographer Pina Baush and her company

- Einstein on the Beach directed by Robert Wilson with music by Philip Glass

- Achterland by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker (Rosas)

- Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker (Rosas)

- Transverse Orientation by Dimitris Papaioannou

Leave a comment