Mar 2023 | Presentation at Cultural Studies Association Taiwan annual conference and Department of Architecture, NCKU.

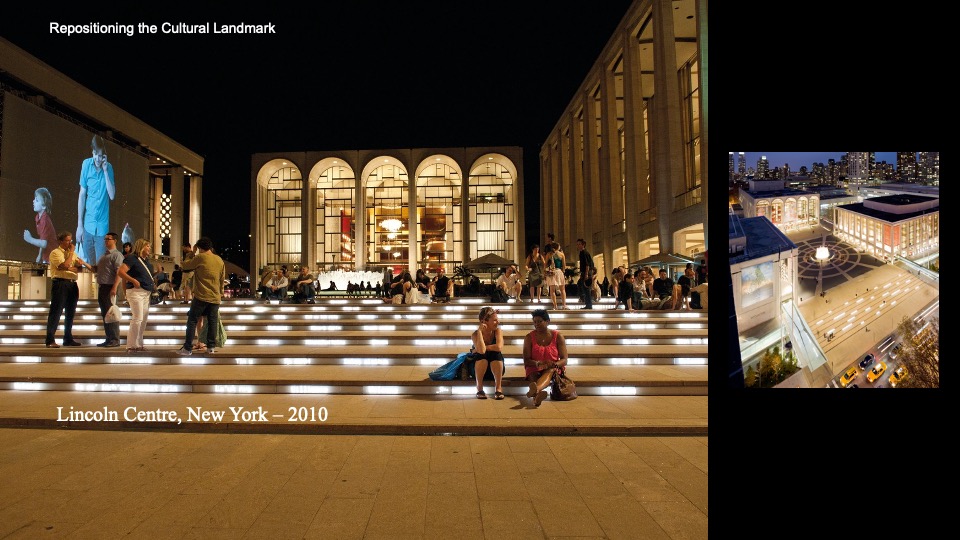

Our understanding of “cultural infrastructure” is usually the landmark architecture like the museum or the opera house, such as the Lincoln Centre in New York City constructed in the 1960s. It is a grand structure sitting on the high plinth as a “cultural palace”, which is isolated from the urban context and public life, represented by well-dressed elites on the balcony looking down into the empty streets.

Since the late 20th century, the question of the value of culture and who it serves has been a critical debate in both research and practice relating to cultural development (Holden 2006), leading to many public cultural institutions reviewing and reforming their positioning in the past two decades (Gielen 2013). In the case of the Lincoln Centre, it is manifested through its public space, which began as a small plaza renovation project in 2000 and developed into a comprehensive re-design of its public realm over the next 10 years. Working closely with the Lincoln Centre administrators and other stakeholders, the architecture studio DS+R proposed the concept of “inside-out” to turn the internalised cultural space outward with an aim to improve its public interface and accessibility (Diller Scofidio 2012). For example, the unwelcoming entrance step to the plaza is extended into a gentler slope with wides steps that cover the vehicle drop-off, reaching out to the sidewalk and reducing the physical barrier for pedestrians to arrive at the main plaza. Together with public programs such as summer outdoor screenings or performances, people and leisure activities are brought from inside the building to the public space and surrounding area. This is an example of how spatial design act as an agent of change.

The Hong Kong Cultural Centre (HKCC) was conceived in a similar model to the Lincoln Centre. It is designed to be a cultural landmark to represent a world-city image, fitting the rising status of Hong Kong during its economic boom in the 1970s. While many cultural institutions established in the late 20th century are now reconsidering their role and positioning in cultural development, Hong Kong seems to remain in the old paradigm of celebrating grand architectural objects and prioritising visual quality. The currently still-developing West Kowloon Cultural District (WKCD) is a master plan that is 5 times larger than the HKCC, yet still follows a similar approach as a series of landmark objects on the field of the waterfront park, with very little consideration and connection to the surrounding urban fabric and public life. Three decades after the HKCC’s opening in 1989, the role of the prime cultural venue in Hong Kong is shifting to the WKCD. It is now a timely opportunity to review the HKCC’s public positioning — what would be the question to ask as we examine culture from a spatial perspective?

The question of cultural space and participation

Global and local social changes in recent years have presented an opportunity and urgency to rethink public space, which can be extended to the question of cultural development through the framework of spatial agency for public cultural participation. To observe social distancing protocols during the pandemic, activities from dining to recreation are brought outdoors and taking over the streets. It was an unintended prototyping exercise of how public space can be used and reiterates its essential role in urban life. The cultural sector is also facing challenges and opportunities as indoor venues are closed, forcing cultural practitioners to consider alternative performance outlets. Other than the virtual space, much attention was put into exploring the use of local open space for cultural activities, not only to move performances outdoors but new forms of creative work in public space also emerged. While the original intention was a contingency response to venue closure, the result effectively took culture out of the institutional “palace” with a stronger public interface, contributing to the cause of cultural participation. How do we make space for culture?

The focus on space also brings the public person to the foreground as the protagonist of cultural activities. Different from the auditorium setting that dictates the performer-audience relationship, when public space becomes the stage of cultural acts, the public is no longer in a passive observant role but an active participant through their responsive action. Furthermore, although it is not the subject of this presentation, the recent social movement in Hong Kong demonstrated active public participation and how the cultural landmark is turned into a public space for civic action. The post-movement reality in Hong Kong has put public (and cultural) activities into a vulnerable position, as the authority exerts more stringent control in public space – therefore, the creative citizen will need new ways to consider participation in cultural and public life. In the following analysis, we will look at the HKCC not as an object but as an inhabited space to investigate the spatial agency for inclusive cultural development.

The cultural public space typologies

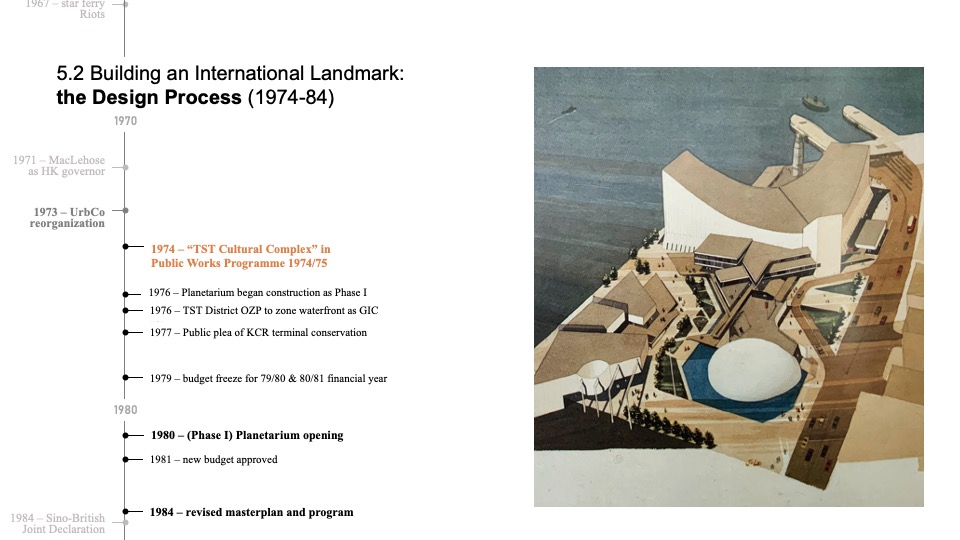

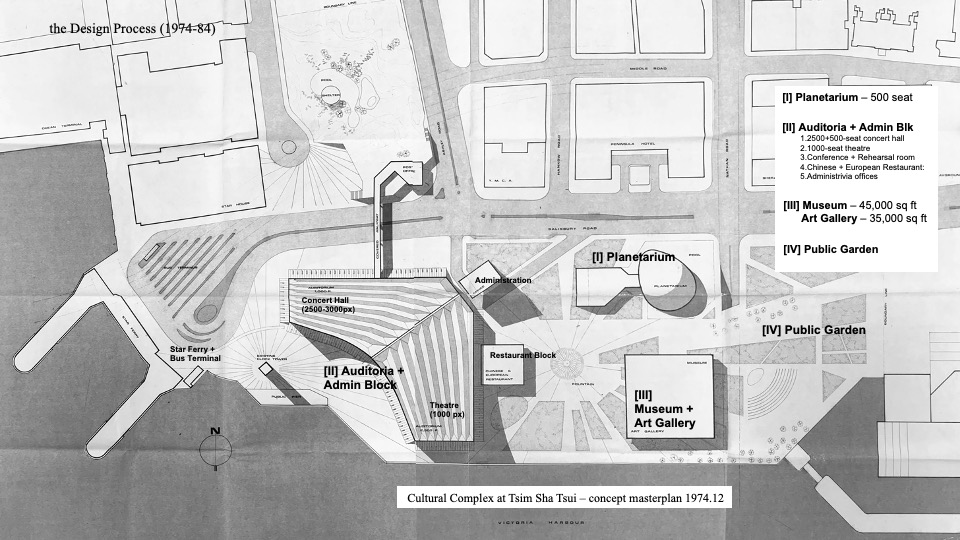

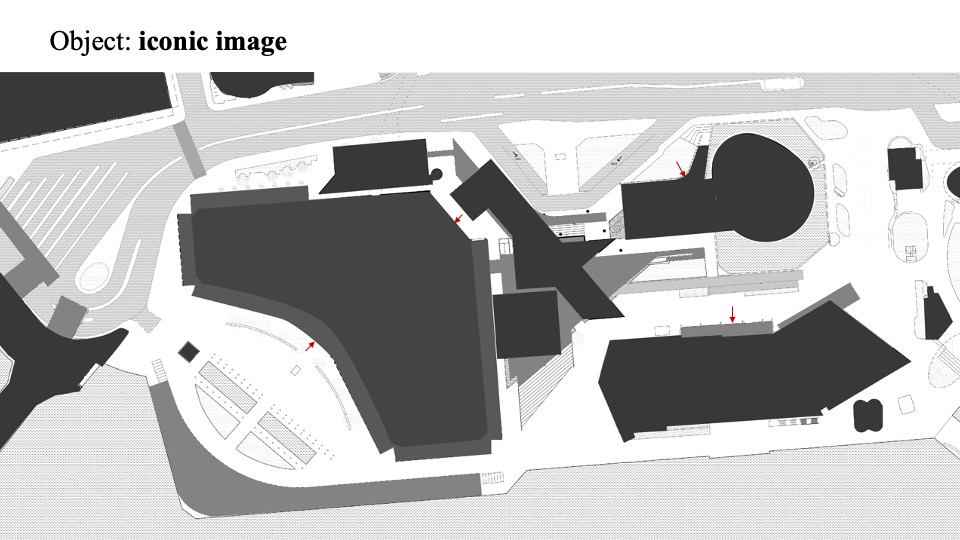

The discussion regarding the need for a new cultural centre for Kowloon began in the 1960s and took over two decades to complete. The first design concept was revealed to the public in 1974 and remains essentially the same as how it was eventually built 15 years later. This drawing of the original masterplan shows the three distinctive architectural objects (the Space Museum, the Auditoria Building, and the Art Museum) on the waterfront site. As suggested by Rowe and Koetter in Collage City, these buildings are “space occupiers” that consume surrounding space as a field (or a backdrop) instead of a “space definer” that defines and creates urban space. It can be read more clearly as a figure-ground drawing that highlights the architectural object with the purpose of projecting an iconic image.

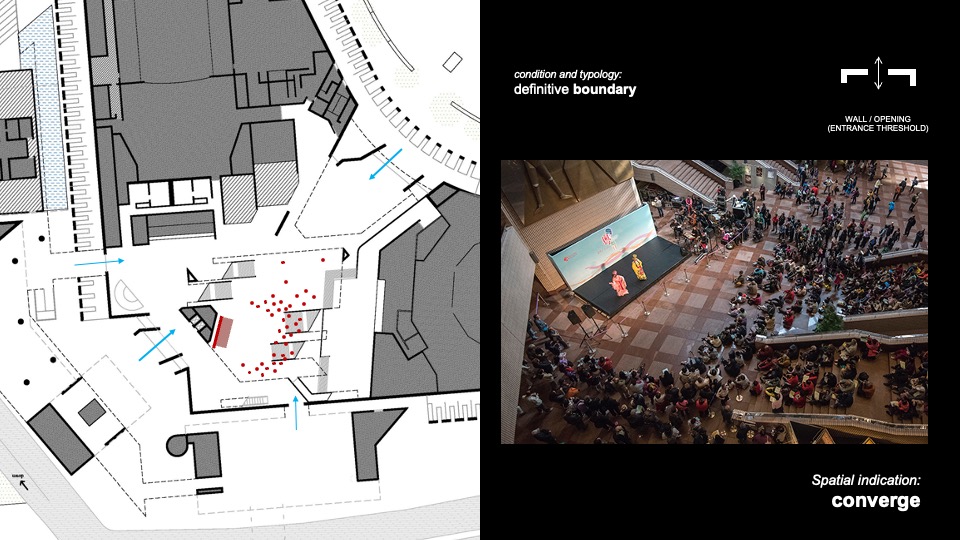

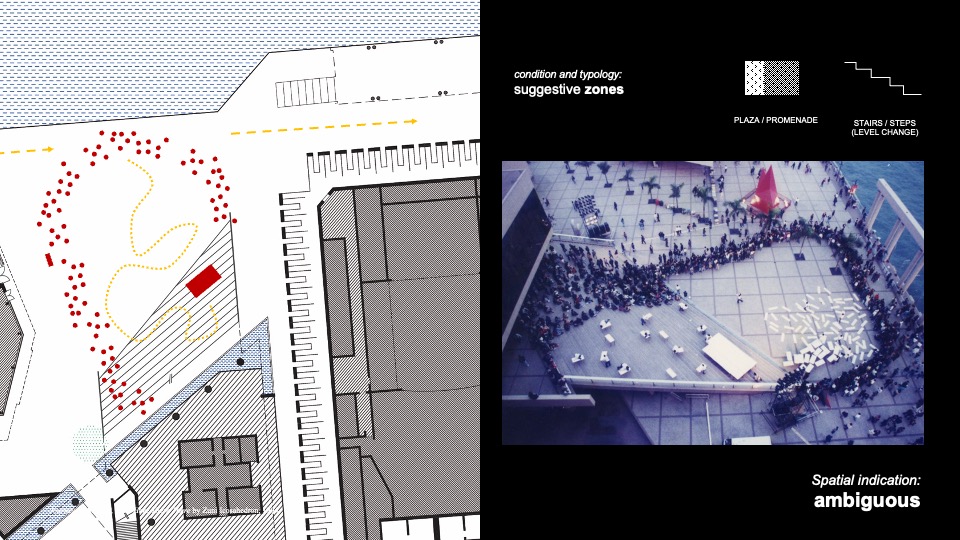

However, a different reading closer to actual spatial experience is revealed if we adopt the Nolli Map method to redraw the plan as a figure-ground of accessible public space. The Nolli Map originated in 1748 as a cartographic representation of Rome, which denotes public space as void and private space as solid, accounting for both exterior as well as accessible interior. It shows public space as a continuous flow across the building threshold, which is instrumental for the discussion of spatial accessibility and permeability. In this view, the space through the HKCC Auditoria Building is connected with surrounding fragment spaces, forming an accessible public space network that has a more complex quality than a singular open space. The design of different spatial instances represents a varying level of control, demonstrated through its spatial typology and the public activities that took place.

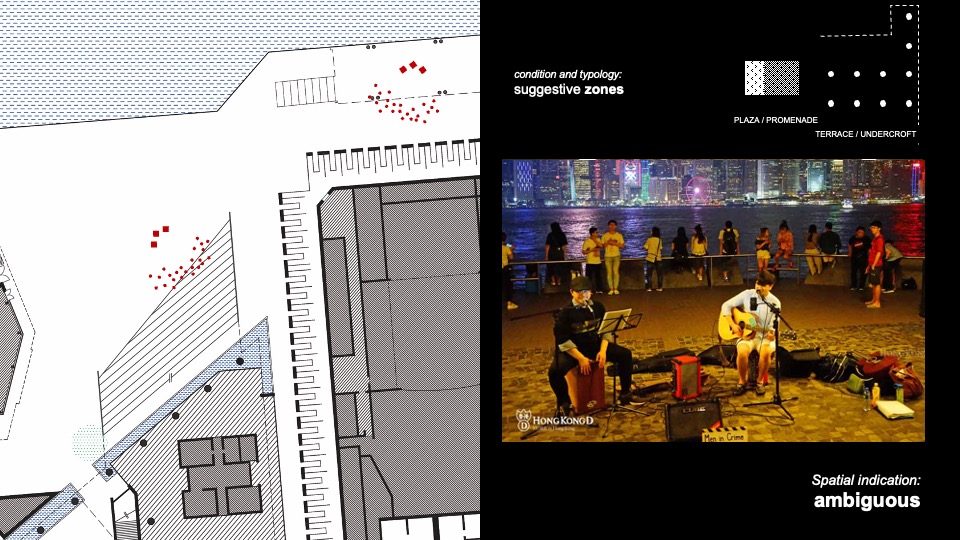

While this study is specific to the HKCC, the extracted spatial typologies and their implications are also applicable in other cases of public cultural buildings. The three categories of boundary, border, and zone describe the spatial characteristics and construct a matrix of typologies when setting set against the indication of convergence, directional, and ambiguous space, which suggest a “tight” or “loose” quality in relation to control and public participation (Franck and Stevens 2007). The review of the different cultural activities at the HKCC public space demonstrates a contrast between the convergence foyer space and the ambiguous plaza and promenade. The foyer space is a boundary condition defined by the threshold and easily controlled, while the open space is a zone condition with a more liberal spatial indication. The performance staged in the public interior (foyer) has a one-way performer-spectator relationship. At the same time, informal cultural acts such as busking or street dances on the promenade blurred the distance and distinction between the performer and viewer, allowing for a more interactive response.

In between the defined boundary and ambiguous zone is the border condition. There is a subtle but essential difference between the boundary and the border, as suggested by Sennett in his recent writing on the idea of Open City (Sennett 2018). The boundary separates conditions through a controlled interface, while the border is an edge where different conditions meet that encourages more interaction resulting in a vibrant environment. Therefore, the border typology has more opportunities for participatory cultural activities with a quality of loose space, such as the under-terrace passage or the outdoor steps at the HKCC. Currently, these are underused transitional spaces sometimes occupied for leisure activities or social gatherings, yet these spaces can be further utilised for participatory cultural performances.

Public space as cultural infrastructure (a proposal)

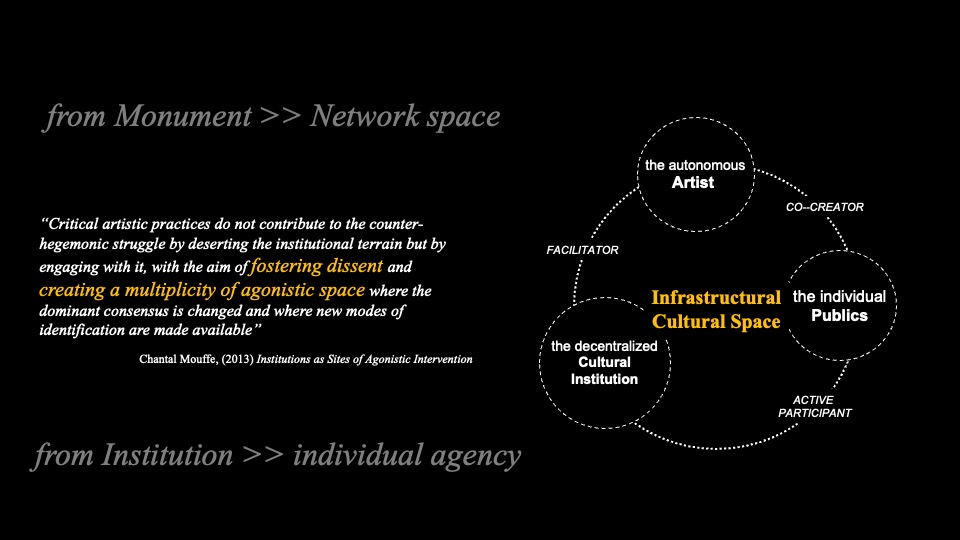

The purpose of the detailed examination of space and activities at the HKCC is to extrapolate the condition allowing inclusive and creative cultural actions. This study concludes with a proposal to reconsider cultural institutions not as a monument but as a network of spatial instances. There is the opportunity to build upon smaller public space units to build a network that function as cultural infrastructure. The individual units are more resilient to changing circumstances, which is suitable in situation that requires adaptable strategies to uncertainties in urban conditions.

The monument is a manifestation of the institution, representing a centralised institutional model that sees cultural provision as a one-way from the producer to the audience. Therefore the network cultural space proposal suggests a change in the reliance on institutional provision to the emphasis on individual agency. The proposal is to decentralise cultural institutions and take on a facilitator role supporting autonomous artist creation. The artist will not only be a cultural experience producer but also engage in co-creation with the public participant. It also requires the public audience to grow beyond a passive cultural consumer to become active participants who also give feedback to institutional operations. Therefore the small-space network is the practice of multiple individuals, as a whole, to form a cultural infrastructure that interrogates what individuals can do instead of waiting for institutional provision. This presentation shared an initial idea for upcoming research on Public Space as Cultural Infrastructure to seek a model for cultural development that would fit the contemporary urban conditions in Hong Kong and beyond.

Reference

- Diller Scofidio, Renfro. 2012. Lincoln Center inside out : an architectural account (Damiani: Bologna, Italy).

- Franck, Karen A., and Quentin Stevens. 2007. Loose space : possibility and diversity in urban life (Routledge: New York).

- Gielen, Pascal. 2013. Institutional attitudes : instituting art in a flat world (Valiz: Amsterdam).

- Holden, John. 2006. Cultural value and the crisis of legitimacy : why culture needs a democratic mandate (Demos: London).

- Sennett, Richard. 2018. Building and dwelling : ethics for the city (Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York).

Leave a comment