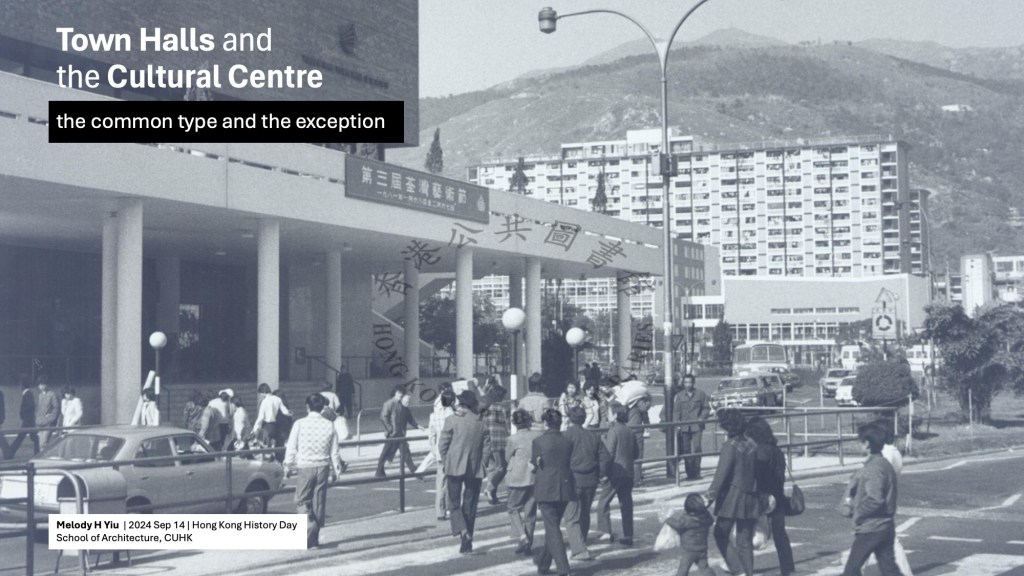

Presented at the Hong Kong History Day 2024, Hong Kong |

Built to achieve a “balanced lifestyle” for living and working, as well as leisure, the new towns are planned with amenities such as parks, sports grounds, and cultural facilities — the town halls. My sharing today will be about the cultural buildings of the 1980s, known by different names: the Town Hall / Civic Centre / or Cultural Centre. In essence, they are collectively a common type — which has greater significance as a concept that can propagate rather than individual architectural objects. Furthermore, instead of being an exclusive palace of arts, the cultural centre as a typology has an inherited social purpose — as a community place that brings “culture” to the public, referring to the paradigm of democratisation of culture in welfare state cultural policy.

During the last decades of colonial rule, a dozen of these cultural centres were planned and built across the territory using an approach of amenity resource distribution. Together with museums and libraries, they represent an ambitious development scheme by the Urban Council (and later Regional Council) to bring access to cultural activities to all parts of the territory. This map shows the spatial distribution of cultural facilities, which are synchronised with urban development in the late 20th century.

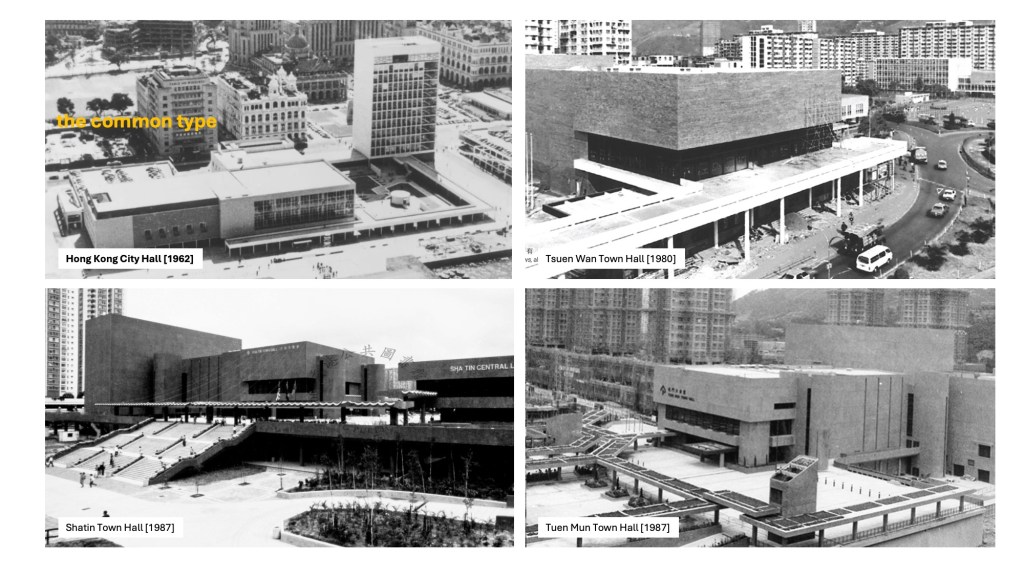

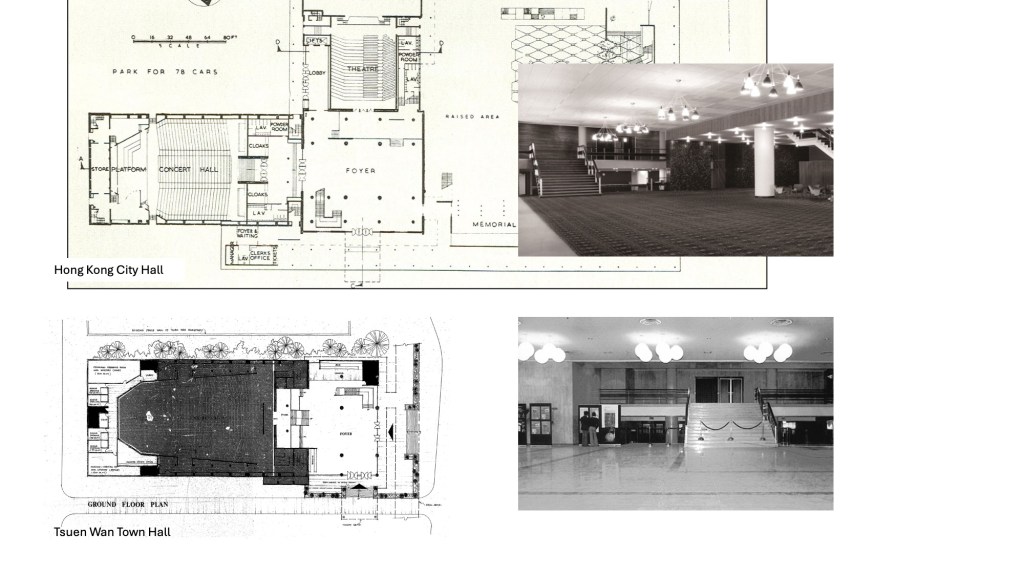

The city’s first and most prominent cultural buildings—the city hall and HKCC—are concentrated in the city across the Victoria Harbour. It is then dissipated to the urban districts with civic centres built in the 1980s. In parallel are the new town development in the 70s/80s, three major Town Halls were built in the first three new towns – Tsuen Wan, Shatin and Tuen Mun – plus a collection of smaller cultural facilities in the New Territories. All these municipal cultural centres were designed by the Architecture Office of the Public Works Department (PWD). It was a technocratic exercise of public building design derived from a stand brief and process, which saw no differences between schools or cultural centres.

Although there was no explicit reference, the early PWD Architecture Office, led by British architects, adopted the UK system in municipal Arts Centre planning and design. The UK Arts Council, established in 1945, suggested that townships with a population of 15-30,000 have a municipal Arts Centre programmed with an all-purpose auditorium, exhibition space, large restaurant, and studio and rehearsal rooms.

These became the standard program for the municipal cultural centres in Hong Kong but for a much higher population ratio. If we take the auditorium size as the benchmark:

- Civic centres with a 400-seat auditorium are planned for districts with 100,000 population, and

- Town halls with a 1500-seat capacity for new towns with a 500,000 projected population.

It is a rational approach to amenity planning that decides resource distribution according to district growth prior to any artistic or curatorial consideration.

Therefore, the common type is a product of a pragmatic solution to fulfil building programs in the most cost-effective and efficient manner, often known to be architecturally unattractive. The first “common type” cultural centre built was the Tsuen Wan Town Hall. After its opening in 1980, other district councils also wanted their own town hall, resulting in the Shatin and Tuen Mun Town Halls opening in 1987. The Tsuen Wan Town Hall was an answer to local demand for a “community hall.” They wanted something within 2-3 years (not ten years), and the only way to do it was to adopt an existing design—which would be the City Hall in Central.

The City Hall, opened in 1962, was the first modern public cultural facility in Hong Kong, which has become the archetype (a standard) for many other public cultural buildings. At that time, the PWD AO was swamped with the high demand for public construction. With a problem-solving spirit known among the HK civil servants, the City Hall architectural plan was directly adopted in the early town halls to save time in designing and preparing construction documents. Therefore, the architectural production of the common type was a pragmatic operation instead of a creative invention, with minimal iterations to accommodate site conditions or minor improvements.

The European vision of building cultural centres saw cultural participation as a form of political empowerment, but the late colonial government considered it a sensitive issue. Instead, they emphasised the rhetoric of community building, strategically avoiding political and ideological references in their cultural presentations. This also had a practical objective during the early new town development—to build a local sense of belonging against conflicts and resistance.

Under this unified system of cultural centres, there was one exception – the HKCC. Situated in the urban centre of the rapidly growing Kowloon peninsula, it was initially planned as the Kowloon Civic Centre (1969), with a standard program similar to the Town Halls. However, for its prime location at the TST harbourfront and the Urban Council’s growing ambition since its organisational reform in 1973, it gradually rose to the status of a new cultural landmark for Hong Kong—and was renamed “the Hong Kong Cultural Centre” in the 1980s. It became an exception that grew out of the common type.

The TST Cultural Complex had an expanded scope and programme, consisting of four components that can be traced back to an earlier project/proposal:

- the Auditoria Building, which was the original Kowloon Civic Centre, with a 2500-seat concert hall, a 1500-seat grand theatre, and a 400-seat studio theatre;

- a Planetarium, a project approved before the conception of the cultural complex by the recreation and amenities committee in the 1970s;

- a Museum of Art, which follows the original expansion plan of the City Hall Museum in 1965;

- and a public garden, the land plot that was designated in the 1969 OZP as a “public open space”

This cultural complex plan was the territory’s prime cultural venue for many years until the gradual completion of WKCD venues.

Unlike the “factory production” of nominal public buildings designed by the PWD AO, the Hong Kong Cultural Centre (HKCC) design was given special attention. It was designed by the then-senior government architect Jose Lei, who later became Director of the Architectural Service Department (ArchSD). In an interview at the time of the HKCC opening, Lei recalled it as the “commission of the lifetime” for him. Although the brief given was just a standard program for a generic cultural centre, through his acquaintance with Urban Council chairman Sales, he recognised the significance of this project, which would require a “memorable form and image.” It carries an ambition as the landmark of the aspiring global city, benchmarked to the well-publicised waterfront Sydney Opera House opened around the time of the HKCC’s conception. It was an invested endeavour of almost $500 million, with the engagement of expert consultants, from structural engineers to theatre and acoustic specialists. Lei selected a team of young local architects dedicated to overseeing the lengthy process of its design development and construction.

The opening in Nov 1989 was a spectacular event that suited the positioning of the cultural landmark. It was opened by then-Prince Charles and Princess Diana, with a month-long inauguration arts festival by renowned artists from around the world. It was well covered in both English and Chinese press: the SCMP produced a 10-page special supplement to celebrate the occasion, and even the New York Times had a half-page report in December 1989, marking it as the most important event in urban and cultural development in late colonial Hong Kong. It was dubbed “the last gift from the colonial government to the territory.” However, it has also received many complaints and critique. Many questioned that its concert halls were uncomfortable despite of the high construction cost. And its windowless form and the “bathroom tiles” on the façade are criticism that we would still hear nowadays.

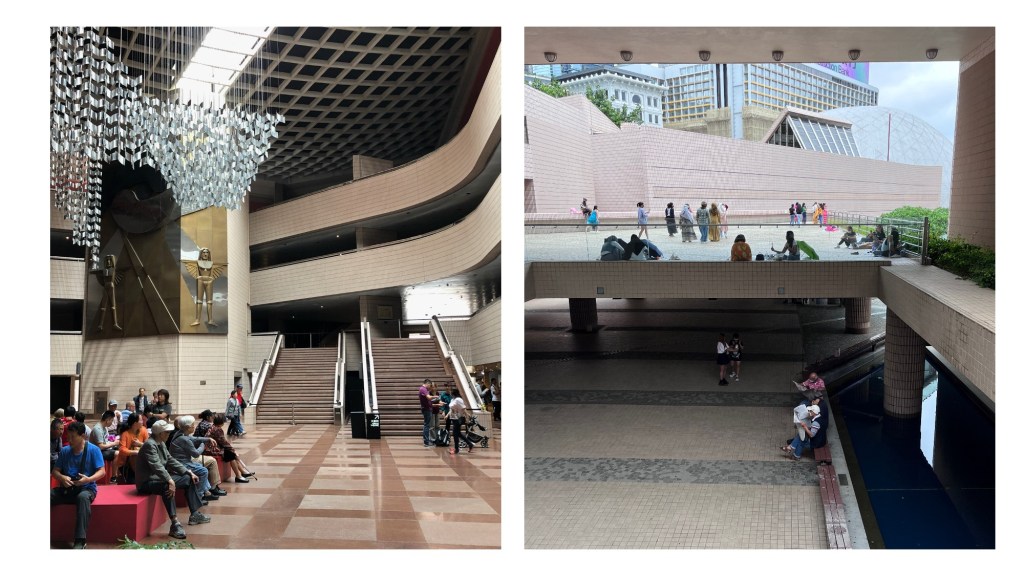

Almost 45 years after its opening, especially now as the limelight all falls on the WKCD, where does the HKCC stand? Furthermore, what role does it play in HK’s cultural and everyday lives? With this presentation, I wish to offer a different perspective on reading landmark architecture, shifting the focus from form and symbolism to space and use in the urban context. This brings us back to the idea of the common type, as the cultural centre typology was conceived as a public space embedded in everyday life.

A key design objective of the HKCC was to create public space against the elitist concept of a “cultural palace.” This objective is manifested in design strategies, including (1) the continuation of the façade tile into the interior atrium and (2) the design of a terraced plaza to convey the civic quality as a place to be used by citizens, whether they are cultural audiences or not. Nowadays, the atrium has become a popular passage to the waterfront, where many people would take a rest there during the hot summer days. The terrace has also become a favourite spot for weekend gatherings by some domestic workers. The HKCC is undoubtedly a postcard image of the Kowloon waterfront, and over the years, it has also become a part of the city that is well-used, and arguably loved, by the people of Hong Kong.

Leave a comment