Presented at the NTUA Conference 2024 Dialectics of Cultural Values: Dialogue and Practice, Taipei |

This presentation draws from my ongoing research about cultural architecture and public life – specifically, the typology of the CULTURE CENTRE. While debating about the dichotomy of cultural architecture as a “palace” for elites – or – an everyday space for the greater public, the question is, in fact, what value culture has to society. With this, I hope to share from an architecture perspective of the cultural development in late 20cHK, and to invite broader discussion on the value of culture.

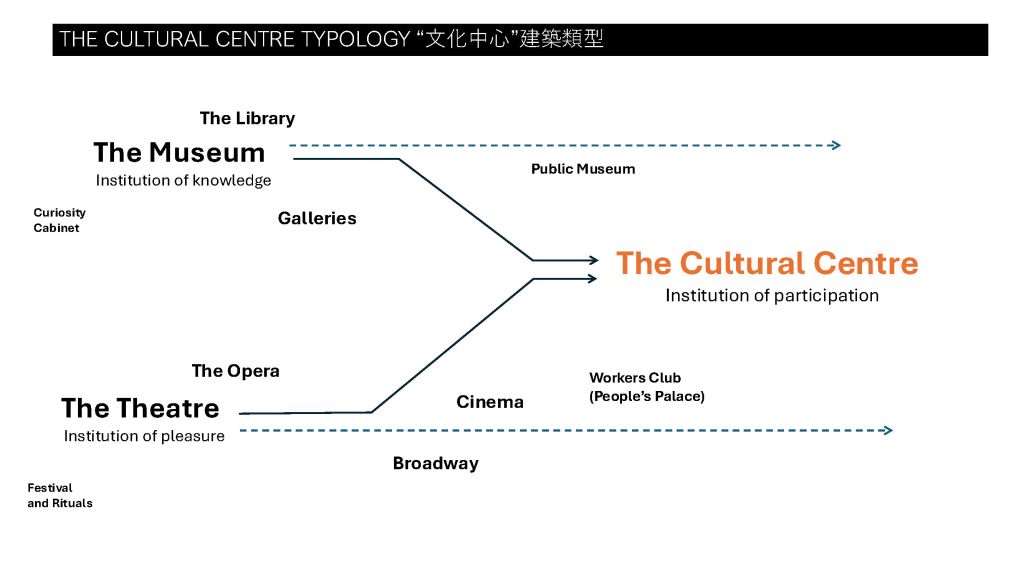

Unlike the archetype of the Museum or the Theatre, which have a long history of artistic or intellectual pursuit, the CULTURAL CENTRE is a relatively new building typology that emerged in the late 20th-century European welfare states. As part of the post-war reconstruction effort, it is a form of public institution that marked the start of systematic state support for arts and culture as we know it today. The genealogy of the CULTURAL CENTRE architecture can be traced back to the first public museum (1852 South Kensington Museum), discussed by social reformers who saw it as a tool of public instruction [1]. The other precedent would be the socialist “House of People” in the early 20th century, as a diversion of the public theatre form. Its core program is the auditorium, dining hall and social gathering place, with the notion of a place for public participation [2].

Therefore, the architecture of cultural centres speaks a different language than the expressive monuments of grand theatres or museums. It is a place to bring cultural life and activities to the public – to democratise culture, per se, reflected in the design that emphasises visual and spatial transparency and flexible use of space. The cultural centre was not meant to be iconic architecture but a common type that is standardised, to be duplicated and populated across geography. Since the UK established the Arts Council after WWII, one of the first efforts was to help local municipalities in building arts centres to improve cultural accessibility. The “Plans for an Arts Centre”, published in 1946, illustrates the standard cultural provision for small to medium townships (15-30,000 population). The building program includes an all-purpose auditorium, exhibition space, restaurant/canteen, as well as studio and rehearsal spaces – which fulfil the purpose of being a community gathering space and accommodating touring performances or exhibitions.

Although there was no explicit reference to the UK Arts Council, this standard brief was conveniently brought to HK by the British architects working at the Public Works Departments. Opened in 1962, the City Hall was the first modern cultural centre in Hong Kong, with a combined civic + cultural function for the late colonial territory. The design is a two-block composition framing a memorial garden and encompasses cultural programs of a concert hall, a theatre, a museum and a gallery and civic programs such as the library, marriage registration and public service offices. While earlier efforts to build cultural facilities were mainly philanthropic or commercial, the City Hall marks the beginning of a formal cultural provision by the colonial government.

From the 1970s to 2000, a dozen cultural centres, public theatres, and museums were built in Hong Kong that answered the paradigm of democratisation of culture [3]. It also represented the ambition for urban development during the last decades of colonial rule. Unlike the comprehensive cultural policy in the UK or other countries, cultural centres in Hong Kong were considered a scope of amenity planning within larger housing or new town planning schemes, in parallel to building parks or community centres. The objective was efficient resource distribution, treated similarly to other social provisions, such as public health or education. It is benchmarked by population for standard provisions, a rational approach that artistic or curatorial consideration was an afterthought.

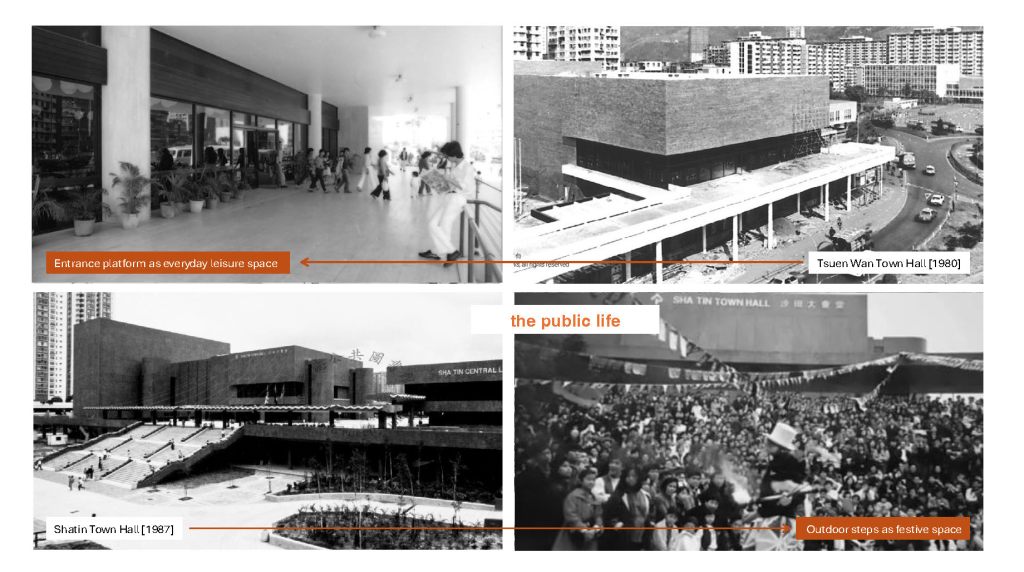

These are some of the first cultural centres built in the 1980s – as “Town Hall” in the new town masterplan schemes. Operated as a technocratic exercise by government architects, the result is the COMMON TYPOLOGY that provides a pragmatic solution in the most cost-effective and efficient manner, which was also known to be architecturally unattractive. Instead of architectural aesthetics, the common cultural centres emphasise its role as the place for public life. It is reflected in the design of its public space and programming, which revolves around local life rather than artistic excellence.

Another typological iteration is the “civic centre” that propagates in the urban districts during the 1980s. Unlike the generous plots allocated for recreation and culture in the new towns, the challenge here is to find sufficient public land in the dense urban district for cultural use. The solution was the design of a compact, high-rise public service building. It integrates the program of a market, a library, sports halls, and an auditorium with the provision of seminar rooms and a rehearsal studio. An example is the Ngai Chi Wan Civic Centre opened in 1987. Located in a dense urban area surrounded by high-density public housing estates, its design has a street-level podium for a public wet market, with three vertical blocks that accommodate the sports hall, the library and the auditorium, respectively.

The three decades of active construction in the late 20th century built the foundation of HK’s cultural service, with a collection of performance space and museums that are still the main cultural venues in use today. Public investment in building cultural centres slowed down in the 1990s. Since the sovereignty change from the British to the Chinese CCP government, the newly established HKSAR government took a different turn in cultural policy. It emphasises culture’s instrumental (instead of social) value, as reflected in the WKCD mega-project and the urban regeneration scheme with peripheral cultural use. For this presentation, we looked at only one fragment of this overall trajectory – the municipal cultural centres. The purpose is to bring attention back to the original social purpose of the cultural centre as a place for everyday life — as a response to the current problem of predominant focus on iconic architecture and the neoliberal approach to cultural development.

The understanding of cultural centres as a common type reveals an infrastructural quality, where the network of public cultural centres forms a constellation of cultural space in the city with a collective impact on everyday life.

According to anthropologist Brian Larkin, infrastructure is “the built networks that facilitate the flow of goods, people or ideas and allow for their exchange over space” [4]. Adopting this view for cultural development, it is not only the large physical structure we see on the ground, but its functioning relies on the substrates of pipes and cables to support it. Therefore, this paper opens a perspective to read cultural space as infrastructure (instead of objects and images), comparable to other public services such as schools or clinics, enabling education or public health. – leading to the crucial questions: What are the pipes and cables in cultural services? How do they work as a system to support cultural development?

Infrastructure is a relational and spatial concept comprising tangible and intangible components – for which we need to read the relationship between objects and their tendency, asking how it works instead of “what it appears to be”. It breaks through the common view that celebrates a universal design for “everybody” and instead looks for the dynamics between different conditions, even though they could sometimes be conflicting. Following the legacy of late-colonial cultural policy and the current economic-priority direction of the HKSAR, the official narrative on cultural development in Hong Kong is still primarily focusing on hardware development and instrumental value in economics. It is important to raise awareness of the intrinsic value of culture and construct a framework for diverse and inclusive cultural development. While the new constructions at the WKCD will be taking over the dominating role as the city’s prime cultural venue, the infrastructural approach offered in this paper can be viewed as an opportunity for the cultural centres to recalibrate its position as an everyday space of quotidian culture, working as spatial units within a larger infrastructural network.

Reference

- Bennett, T. (1995). The birth of the museum : history, theory, politics. Routledge.

- Cupers, K. (2022). The Infrastructure of Participation: Cultural Centres in Postwar Europe. In M. Stierli & M. Widrich (Eds.), Participation in Art and Architecture. Bloomsbury.

- Evrard, Y. (1997). Democratizing Culture or Cultural Democracy? The Journal of arts management, law, and society, 27(3), 167-175.

- Larkin, B. (2013). The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure. Annual review of anthropology, 42(1), 327-343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522

Leave a comment